English Teacher, AACPS, MD. July 2022-present

Creative College App Presentation or How to Tell a True College Application Essay

Fourth quarter, the English 11 curriculum for my district involves teaching The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien. Unfortunately, due to testing schedules and Spring Break timing, we haven’t been able to teach the entire book the two years I’ve taught English 11. We also end up with an awkward few weeks at the end of the semester: not long enough to start a big project but too long to just fill with small activities.

My fellow English 11 Honors teacher, who has taught this course for years and designed much of the curriculum we use, assigns a college application essay during this time, so that students have at least a draft before they head off for the summer. Previous years, she also did a creative presentation. I suggested we take inspiration from the value O’Brien places on a well-told story and have students present their college application essays. (Here, for those of you who know the novel, we’re focusing on happening-truth, not story-truth.)

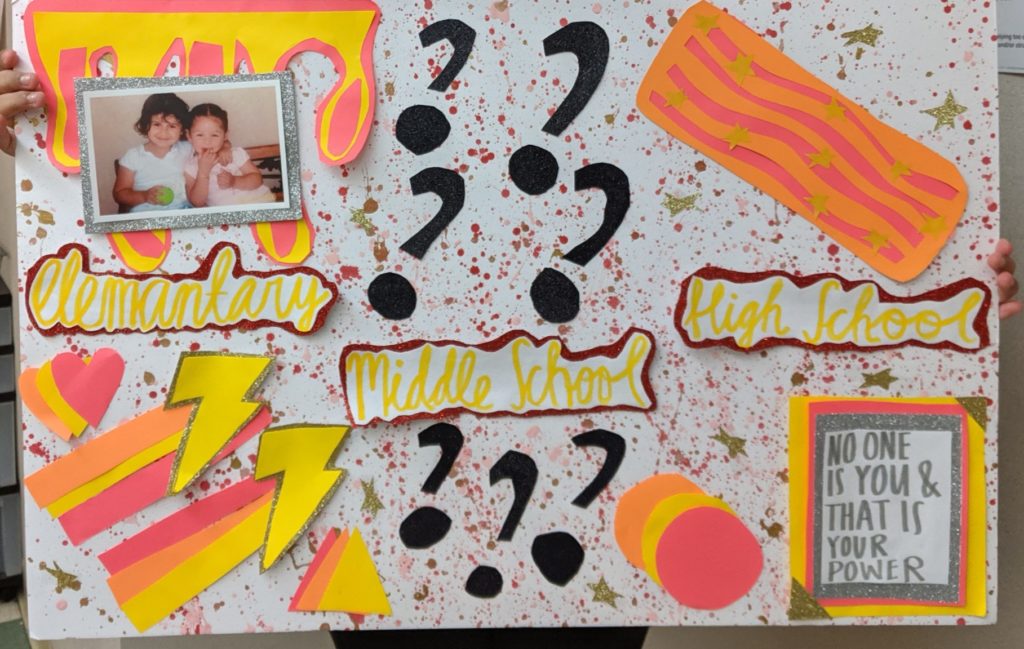

So last year, I designed our final assessment for fourth quarter, which is still in want of a good name. Students take their college application essays and turn it into a presentation that they will give the class. But not just any presentation: a modified Pecha Kucha (aka Ignite*).

A Pecha Kucha presentation uses 20 image-heavy or image-only slides that are on the screen for 20 seconds each (Ignites reduce the time per slide to 15 seconds and the overall time to an even 5 minutes). Rather than focusing on the slides, Pecha Kuchas place the focus on the presenter and, more specifically, the story they are telling. A perfect format. Only, we didn’t have enough time for 32 6:40 presentations. So, I limited the presentations to 15 slides at 15 seconds each, for a more manageable total length of 3:45. Since the slides auto-advance, it is extremely easy to get thrown off, so the format also requires something most students don’t do before a presentation: practice.

Here’s how we scaffolded the process:

- Students draft a roughly 600-word essay answering one of the Common App prompts. This serves a few purposes: gets them a draft of an essay before they need to start applying to college, helps them commit to a topic and organize their thoughts around it, and provides a blueprint of their presentation for the teacher. When I grade it, I keep the end presentation in mind: Do they have a story structure that will work? Are there any details they might not feel comfortable sharing in class or that might be triggering to other students? Can they tell this story through visuals?

- As a class, students watch and evaluate my presentation and examine the process I used. Whenever I can, I dogfood my assignments (especially risky ones), so I introduce the presentation process by presenting my story to the class. Students evaluate me on the rubric: one student always eviscerates it, but most give me a solid B. A fair grade, I’d say.

- Students examine the process that went into creating my presentation. Inspired by the New York Times’ old Annotated By the Author series, I created a process document explaining how I drafted, revised, and practiced my script and slides until I got the timing and pacing right. This helps students understand the amount of work required and, I hope, helps them avoid some pitfalls.

- Students get ready to tell their stories. From here, students spend a class or two scripting their story, creating their slides, and practicing their presentations. The ones who start practicing early realize quickly how smart they are. Those auto-advancing slides seem to move both more quickly AND more slowly than one thinks they will.

And then we come to presentation day. Last year, the presentations were revealing, entertaining, heartwarming, heartbreaking, and insightful. A few were thrown together at the last minute, but the vast majority revealed a truth about each student, often one their peers were not aware of. During the presentations, I saw students discover shared experiences and start to connect in ways they hadn’t before. I was happy because I felt like I had finally found a final assignment that did what I so loved about the Final Word at SVHS: deepen our community by giving students a chance to show their true selves. O’Brien would be proud.

A quick note: At my current school, curriculum materials I create for my job are the intellectual property of my district, so I can’t post the assignment instructions here (I’m 90% sure of this). Just to give a visual, I’ll see if I can post a video of my presentation and my process document.

*Coincidentally, Ignite was cofounded by a high school classmate of mine.

English Teacher, SVUSD, CA. Aug. 2016-2020

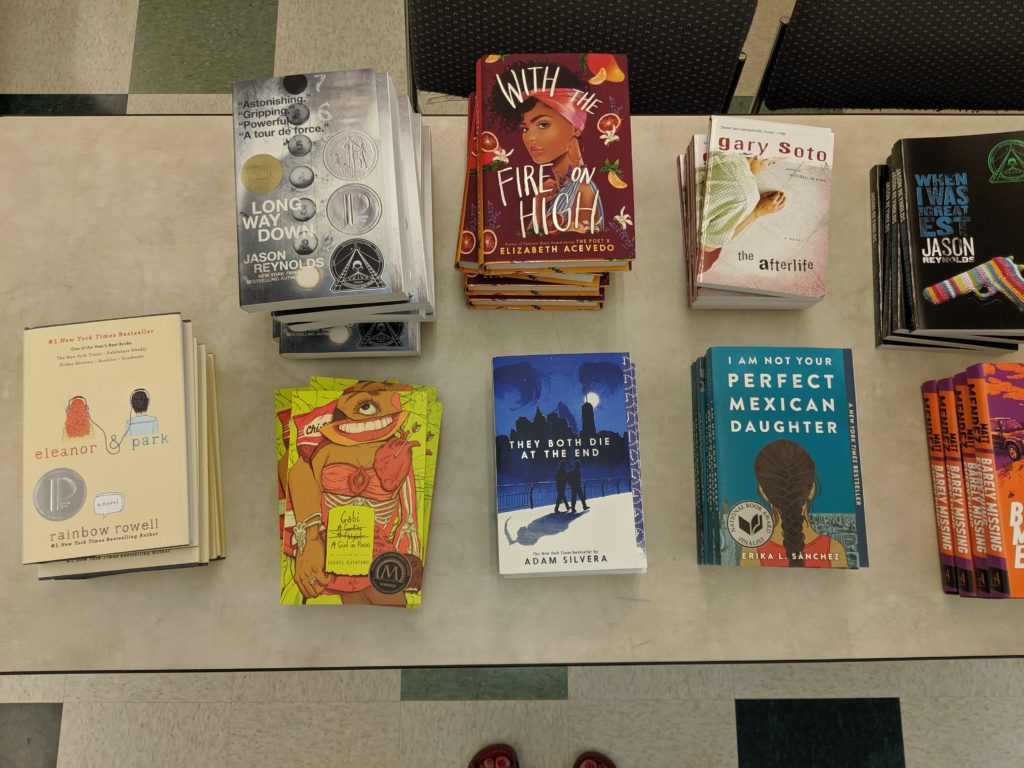

Exploring Identity Through Independent Reading Novels (Aug.-Sept. 2019)

The two essential questions I build my English 2 curriculum around are:

- How do we become who we are? How do we develop our identity?

- What’s our role and responsibility within society?

I decided to start off the year with my College Prep classes exploring the first question through book clubs for independent reading books. Our school is 39% white and 55% Latinx, yet our core novels and plays for English 2 are all written by white male authors and published before 1960. It seemed necessary to explore this question through books that better reflected our student body.

Over the summer, I successfully funded my second book-related DonorsChoose grant, which together brought multiple copies of 13 new and diverse independent reading book titles to my students.

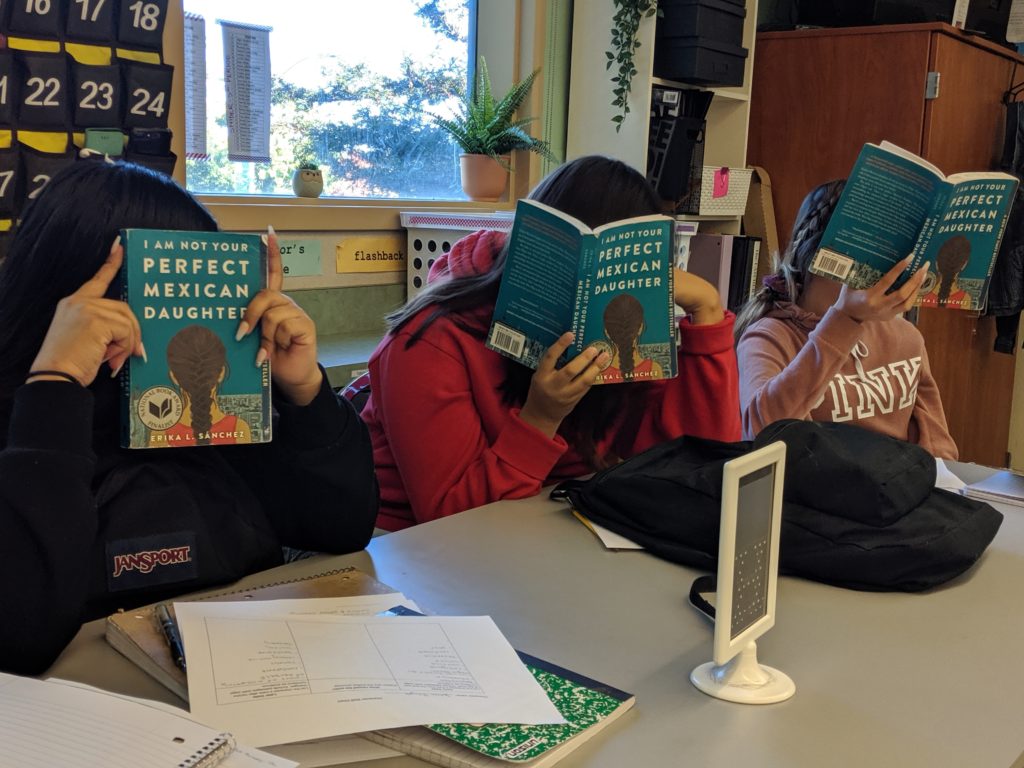

Since my students participated in weekly independent reading book club groups for most of their freshman year, I started off by inviting students to determine the norms for our book clubs, choosing the rules that worked well from the previous year and offering them an opportunity to change the things that weren’t successful.

In the weekly self-directed discussions, students grappled with the issues in the books, helped each other resolve confusion, and shared their favorite moments. Many found themselves connecting to the characters and stories.

My assessments for this unit included:

- An ongoing reading journal. Students were expected to write something about the book every time they read. Each week, the book clubs worked collaboratively to add still more analysis to their journals in the form of identity charts to track the people and things that influence the main character and character shift charts to track how and why the main character changes through the book.

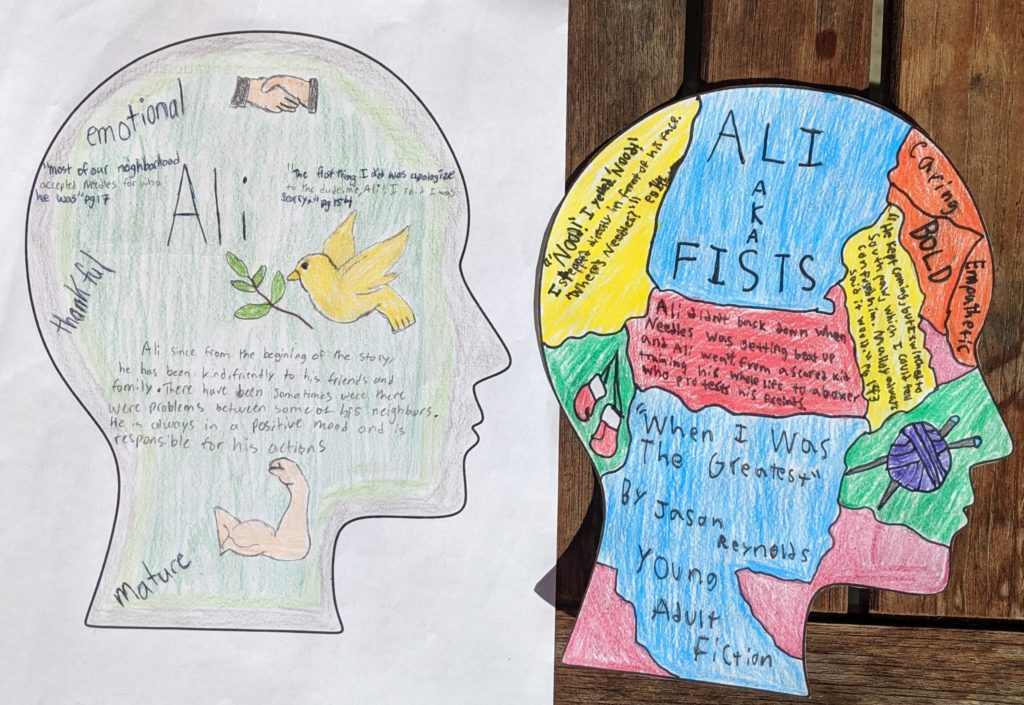

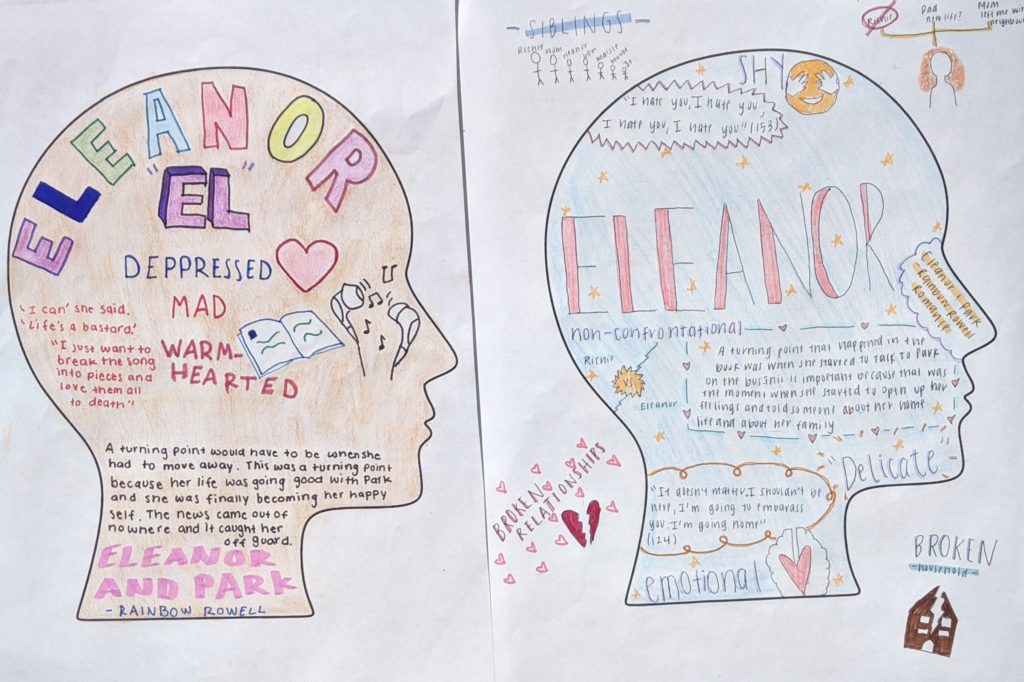

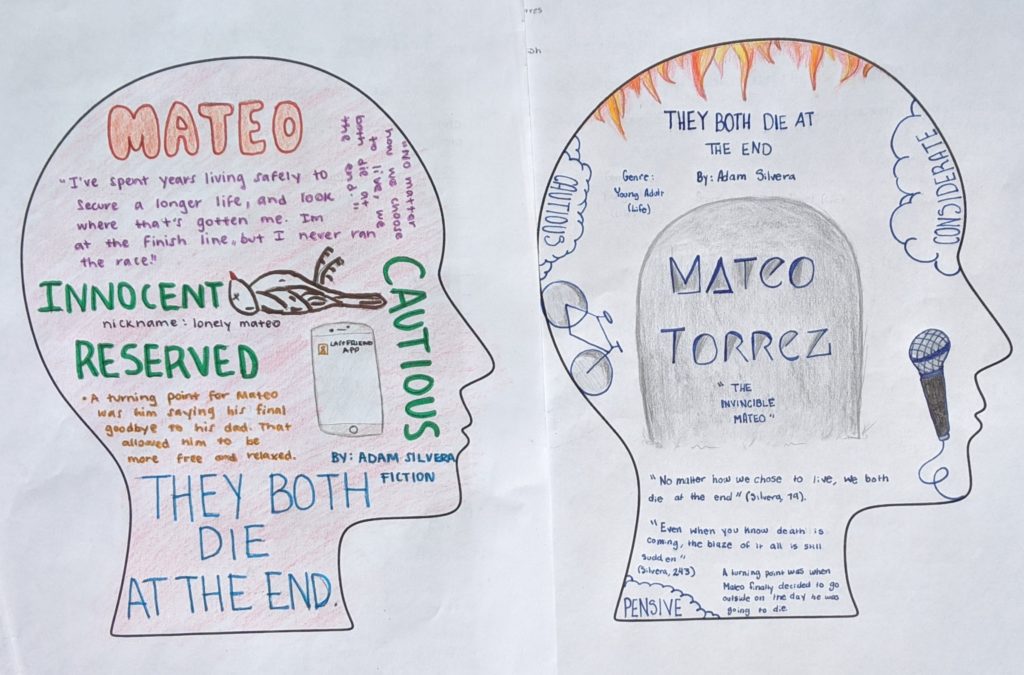

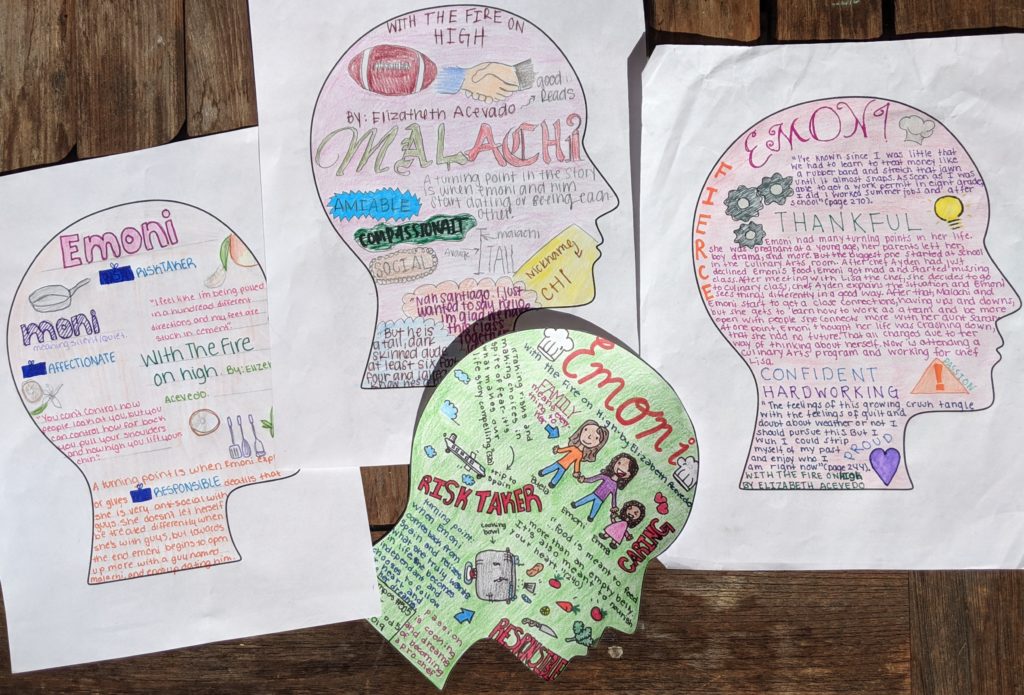

- A character head. This visual project (which I did not create) helped students creatively express their interpretation of the main character’s identity.

- A character shift paragraph. This paragraph grew out of the work we did in class on the identity chart (tracking a character’s influences) and the character shift chart (identifying why and how a character changes through the book). This was an informative early assessment for my students’ writing at the beginning of the year. See unedited excerpts below.

Excerpts from the character shift paragraphs (unedited)

- What made Brianna [from On the Come Up]be a stronger person is society, childhood, school life, home life, and music. The society made her who she is by influencing her to not be as shy and more outgoing, more people started noticing her from her rap battle that went viral and she felt some type of way that she’s never felt before, she felt powerful. Her childhood was pretty rough because her dad was murdered when she was four years old and her mom then turned to drugs and became an addict.

- In They Both Die At The End by Adam Silvera, Mateo changes from being cowardly to thankful and safe because of meeting his last friend Rufus. When Mateo first gets the call, he hides at home. However, he signs up for this app which is where he meets Rufus and that is when things start to change. Rufus brings out this side in Mateo that he never thought he had. This change is first shown when Rufus encourages Mateo to leave his house. Mateo hears a knock at the door and starts to panic.“Different nerves hit me all at once: what if it’s not Rufus, even though no one else should be knocking at my door this late at night?” (89). The reason for all this hectic behavior is caused by Mateo letting his fears take control. He is too busy thinking about worst possible scenarios instead of realizing that not only Rufus comes in peace but also he is there to make a good last day with Mateo.

- In ¨ I am not your Perfect Mexican Daughter ¨ by Erika L. Sanchez, Julia the main character changed from being a self-obsessed to a more open minded person after her sisters death and the occurences that happened afterwards, that would change her life forever. In the beggining of the book Julia is stubborn and would complain about having a perfect sister that she was compared too everyday, she would argue with her parents and was not happy about living in a mexican heritage home. ¨I dont understand why everyone just complains about who I am. What am I suppost to do? Say im sorry ? Im sorry I can’t be normal? Im sorry im such a bad daughter? I’m sorry i hate the life I have to live?¨.

When the unit was over, the last thing we had to do was to write thank-you notes to the donors who made it possible for us to get these books. Here are some of my favorite things my students shared with our generous donors:

- “[I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter] was very sad because some Mexican daughters can relate to trying to be a typical Mexican daughter.”

- “I relate with Emoni [from With the Fire on High] when she talks about her relationship with her dad, and it made me feel that I wasn’t the only one feeling that way towards my dad.”

- “[With the Fire on High] kinda reminded me of my mother and how she was pregnant at a very young age and had a lot of responsibilities to take care of me and my brother.”

- “[They Both Die at the End] made me wonder what I would do with my last 24 hours.”

The Final Word Project

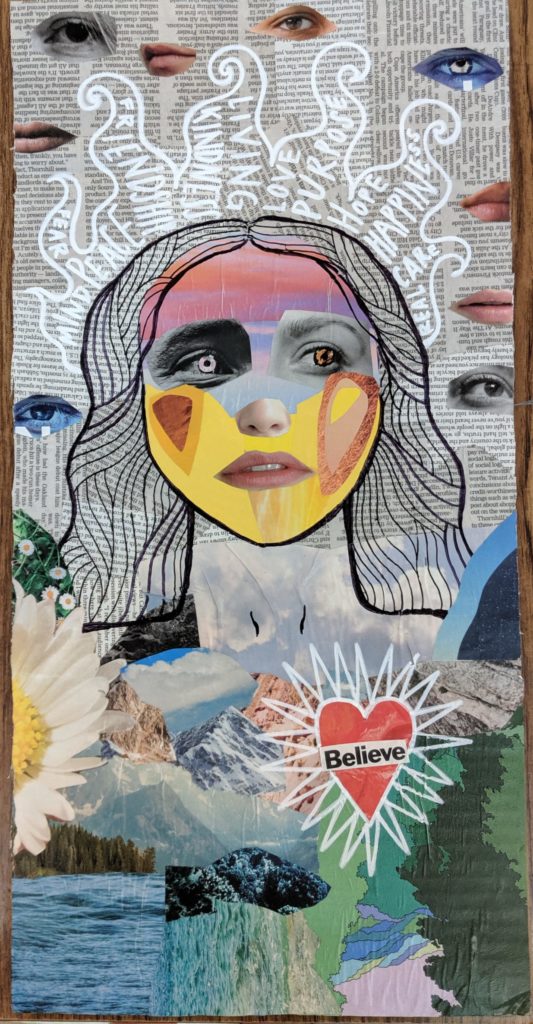

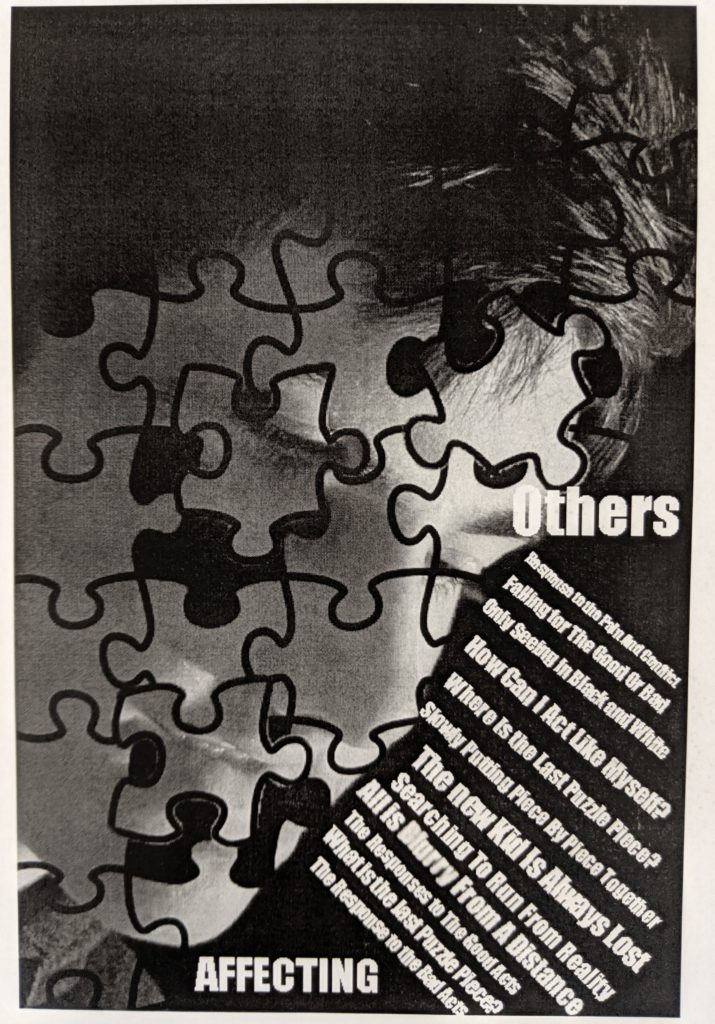

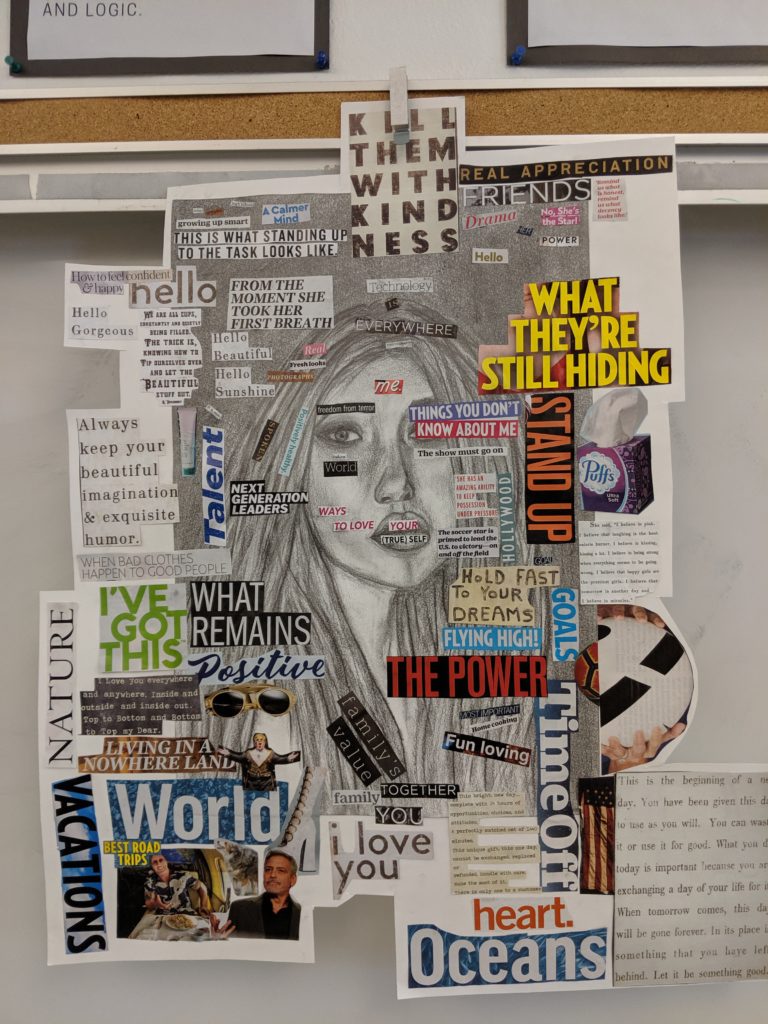

The Final Word Project is my favorite final assignment. It allows students to process all our work on the two essential questions (How do we develop our identity? and What’s our role and responsibility within society?) and to put their own spin on it.

I’ll update this section soon with more details on the assignment but in the meantime, here are some examples of the work that was submitted for the essays and self-portraits that are the culminating assessments for this unit (and the year).

Final Word Essay examples (Note: The 2017-2018 version of this assignment was called the ABU Theme Project):

- Final Word Essay Example 1 (Honors, 2019)

- Final Word Essay Example 2 (Honors, 2019)

- Final Word Essay Example 3 (Honors, 2019)

- ABU Theme Project 1 (College Prep, 2018)

- ABU Theme Project 2 (College Prep, 2018)

- ABU Theme Project 3 (Honors, 2018)

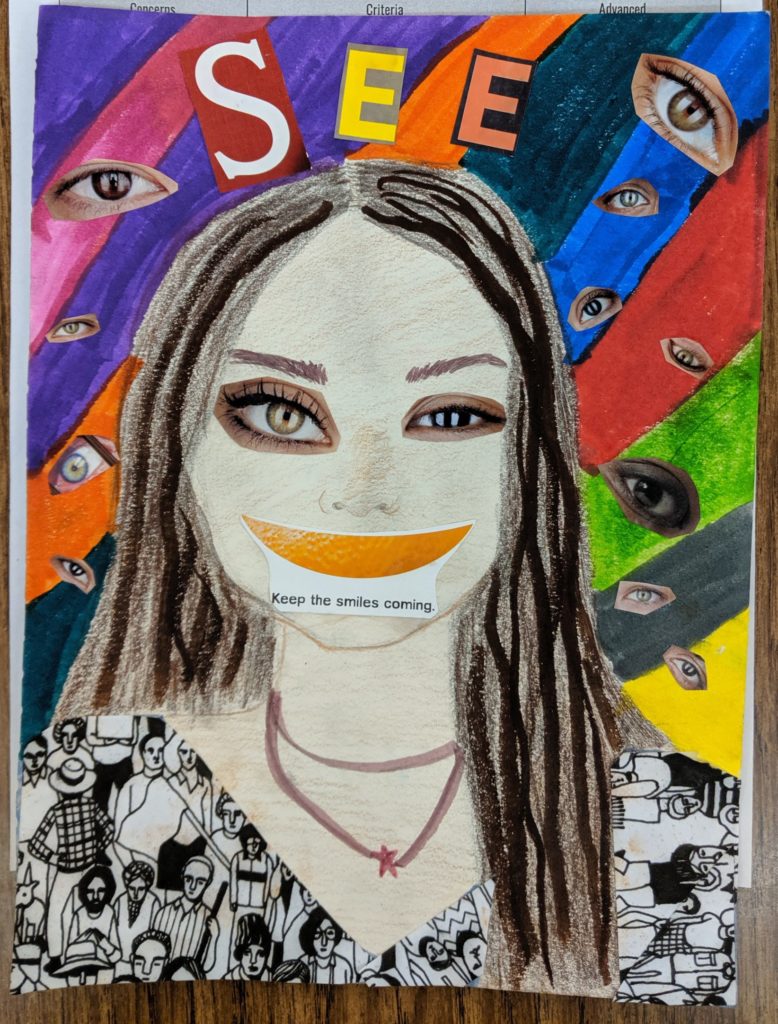

Final Word Self-Portrait, Spring 2019

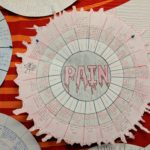

Literary Terms Wheel

Over the course of the year, English 2 students learn 20 (College Prep) or 22 (Honors) literary terms, including simile, metaphor, allusion, apostrophe, and irony. The culminating project is the Literary Terms Wheel, in which students choose a theme (the center circle), list the terms (next circle), write the definitions (next circle), and provide an original example of the literary term that connects to the theme. Note: I did not create this assignment; it has been used at SVHS for years.

2018-2019 (Click on image to enlarge it)

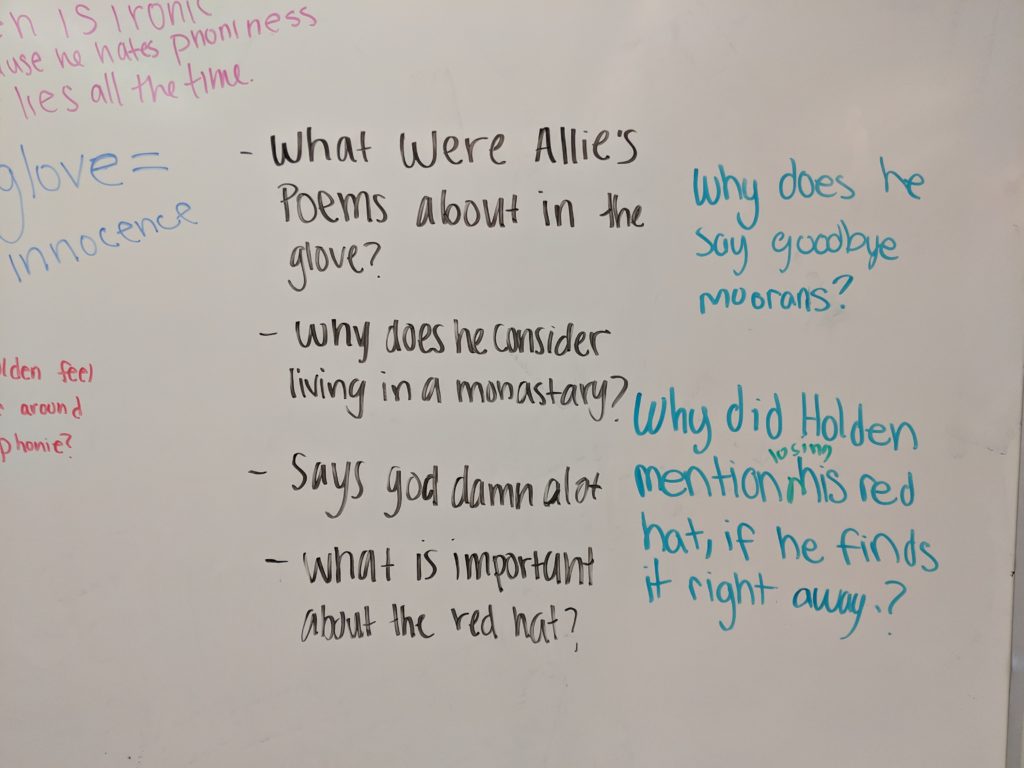

TQE: Thoughts, Questions, Epiphanies

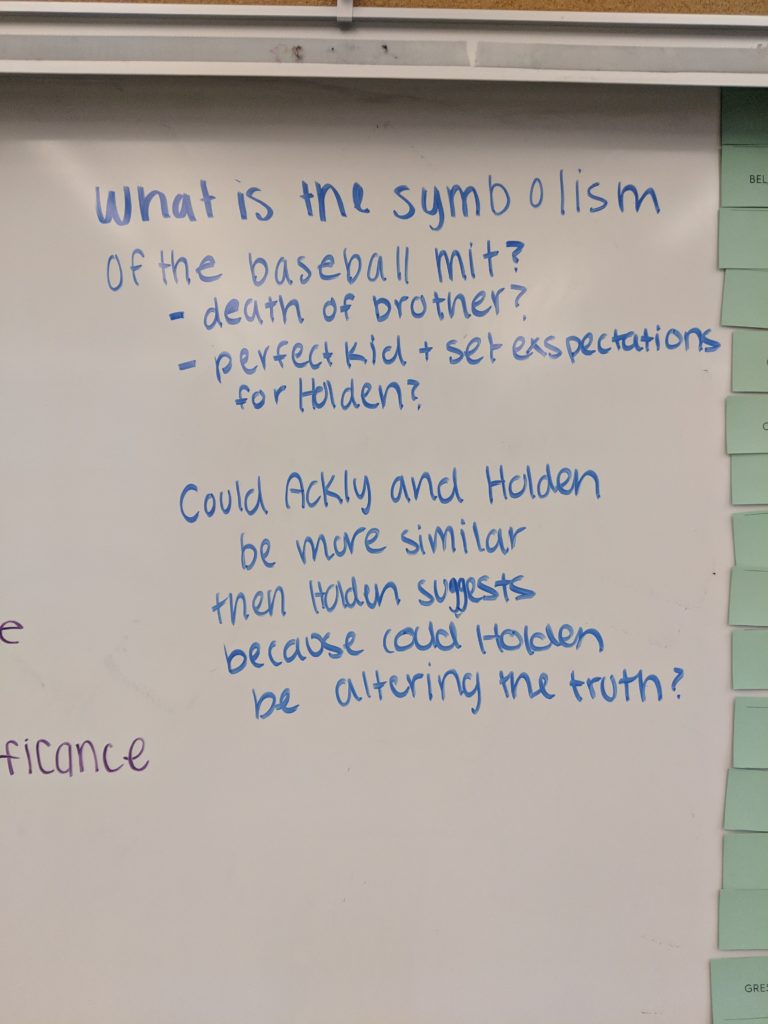

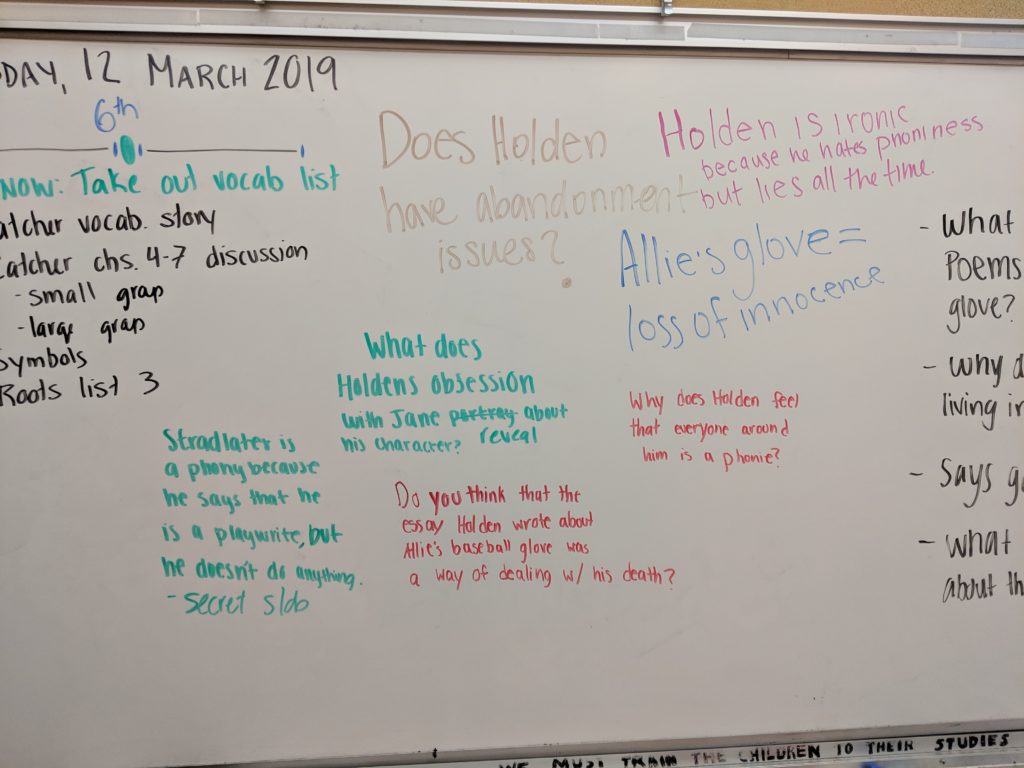

In my first year of teaching, I relied far too heavily on reading questions. After that year, I swore to find activities that would encourage students to dig back into the reading in a more self-directed way. During the 2018-2019 year, I tried Marisa Thompson’s TQE strategy with my Honors classes to discuss The Catcher in the Rye and Night. First, students discuss the text in groups of 3-4 students, using their notes from the previous night’s reading. As they discuss, they use a different color pen to annotate their notes with new insights, questions that arise, or alternate interpretations.

At the end of the small group discussion, each group chooses their top three thoughts, questions, or epiphanies, and then writes them on the board. We then open the discussion up to the whole class, like a Socratic Seminar. A student moderator leads the discussion, starting with the TQEs on the board. I coach the moderator to make sure that he or she keeps the discussion inclusive and moving at an appropriate pace.

Here are some of the TQEs from The Catcher in the Rye, chapters 4-7:

Student Teaching, Kenilworth Junior High, Petaluma, CA. Aug. 2015-June 2016

What it takes to make you great

All seventh graders at Kenilworth Junior High work on an EWRC unit on summary writing that uses an abridged version of the Fortune article “What It Takes to Be Great” as the source. The article is based on a study that found that experts in their fields, like Tiger Woods and Warren Buffet, weren’t necessarily born with natural talent, but had to deliberately practice in order to get great. The study found that this specific kind of practice, rather than innate ability, was what determined someone’s success.

A great message, right? Unfortunately, after the summary was written, students moved on and didn’t have a chance to apply the ideas to their own life. For this age group in particular, I thought it was important to ask them to make that connection. So I designed a two-part assignment in which they would choose some specific area in which they wanted to improve and apply the lessons of the article to come up with a practice plan for themselves. We also added a visual component (a slide, poster, in-class demonstration, or short video) that students presented in front of the class.

As one of the first assignments of my student teaching semester, this was a great way to get to know my students better. But the students also really got into it. For now, I’ve posted my lesson plan as I taught it, which includes some notes on what my mentor teacher and I would have done differently the next time. Someday I hope to edit it to make it more of a final version.

Deliberate Practice Plan lesson plans

What It Takes to Make You Great assignment sheet and samples

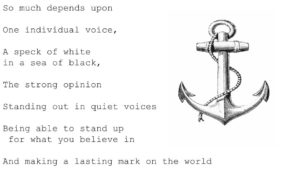

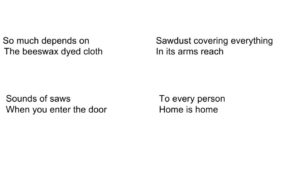

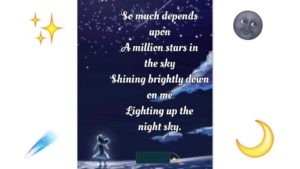

SO much depends: imagery and poetry writing

Many teachers use William Carlos Williams’s poem “The Red Wheelbarrow” as an introduction to poetry writing. It works because it’s effective. I based my lesson largely on my SSU professor Susan Hirsch’s demonstration lesson as well as Corbett Harrison’s many ideas around teaching the poem.

In our poetry unit, this one-day learning segment fell after my mentor teacher introduced the ideas of simile and metaphor by analyzing song lyrics. A few of the elementary schools in our district have very strong emphases on poetry, so some students came into the unit with very advanced analytical skills. Others, however, hadn’t had much experience with poetry. This segment worked for the full range of students.

After reading the poem, I asked students to do a quickwrite, then a quick partner discussion on this question:

- What does this poem mean to you? What does it make you picture, feel, remember, or think?

In phrasing the question this way, and emphasizing the second part of it, students felt free to respond with their first impression. And they had a wide variety of responses, including deep analyses of possible extended metaphors in the poem, photographic descriptions of the scene surrounding the red wheelbarrow, and frustrated questions about what it meant (“I know it has to mean something, but I can’t figure it out and it’s making me mad.”)

I explained Williams’s background and his belief that everyday things could be poem-worthy. From there, we analyzed the structure of the “Red Wheelbarrow” and prepared to write our own “So Much Depends” poems. I asked how many students hated writing poetry, then said, “This is a poetry-writing assignment for you.”

The assignment followed Williams’s basic structure: “So much depends on” followed by three to five short, simple, descriptive lines. Students had the rest of the class period to write.

When students brought their poems in the next class, I was amazed at students’ creativity. Many of these poems were beautiful, with clever word choices that, intentionally or not, implied metaphors and deeper meanings. It felt that, by focusing on such a short piece and heavily structuring the poem, students had enough boundaries to get over the fear of a blank page (“It’s only three images,” I would tell them).

We had students create Google Presentation slides, so they could add more layers of meaning by typesetting and illustrating their poems. Students could opt-out of the class slideshow (or participate anonymously).

Were I to teach this again, I would tie it in with more explicit instruction on imagery in poetry and using all five senses in writing and reading. But overall, both my mentor teacher and I were impressed by the level of creativity we saw in students’ poems and in their slides.

So Much Depends (minimalist lesson plan)

Samples of student work